Atlanta rapper Jeffery Lamar Williams, or “Young Thug,” is in the Fulton County Jail — and has been for more than a year for allegedly co-founding the Young Slime Life criminal gang in Atlanta and is facing racketeering and gang conspiracy charges.

Williams was arrested and charged with conspiring to violate Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations, or “RICO,” Act, after being indicted by a grand jury last May. His label, YSL Records, is being investigated for its possible connections to local gangs.

On Nov. 9, a local judge ruled Williams’s lyrics could be used as evidence in his long-awaited trial, which began on Nov. 27, despite Williams’s argument that the practice would be racist and discriminatory.

One of the song’s, “Slime S***,” lyrics will be used and include the lyrics “Hey, this that slime s***. Hey, YSL s***. Hey, killin’ 12 s***. Hey, f*** jail s***. Hey”; “Cooking white brick”; “I’m not new to this. Hey, I’m so true to this. Hey; I done put the whole slime on hunnid licks”; “Slime or get slimed”; “F*** the judge. YSL, this that mob life.”

The prosecution plans to use the lyrics to draw parallels between Williams’s lyrics and his lifestyle.

They hope to show that he has participated in the unlawful distribution of drugs as well as participated in murder. The use of the word “slime” and hand signals in the videos from some of his songs are being used to show his affiliation with Young Slime Life.

The song they wish to use to prove his involvement is called “Anybody,” and it features Nicki Minaj. It includes the lyrics “I never killed anybody, but I got something to do with that body”; “I told them to shoot a hundred rounds”; “Ready for war like I’m Russia”; “I get all type of cash; I’m a general.”

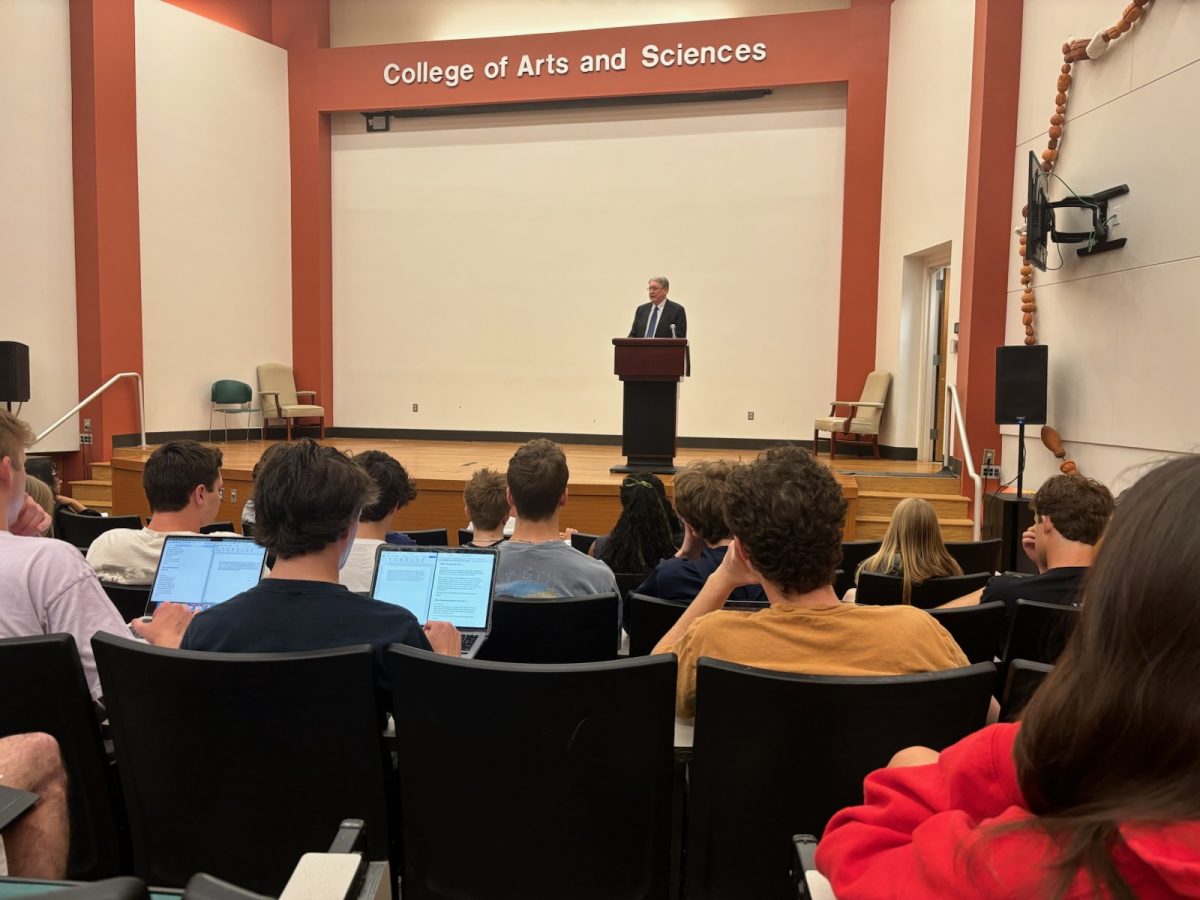

Dr. Andrew Allen, an associate music professor at GC, believes the practice is unethical.

“First, artistic expression has, traditionally, been protected by the First Amendment,” Allen said. “Second, treating lyrics as admissible fact is problematic on its very face. No one believed that the members of Led Zeppelin were gallivanting off on adventures to Middle Earth with elves and hobbits, typical subjects of their lyrics, but anyone writing about real-life situations could now be accused of participating in criminal behavior — even if the behaviors described originated as fantasy or as hearsay.”

Williams’s case is not the first in which a rapper’s lyrics have been used against them. Recent examples include Tay-K and YNW Melly, Meek Mill and even Snoop Dogg, one of the founding fathers of West Coast hip-hop.

Adam Lamparello, a criminal justice professor at GC, compared Williams’s case to former President Trump’s, as both are being charged under the RICO Act, and finds the prosecutor’s citing of the law troubling.

“Prosecutors seem to be becoming more political in who they’re indicting and who they’re seeking to prosecute, and that’s very problematic because the prosecutor yields almost-unfettered, unchecked power to decide who to prosecute and under what circumstances,” Lamparello said.

Dr. Robert Stewart is a music therapy lecturer at GC and sees criminal activity in artists’ lyrics on a similar level to violence in video games.

“I’m thinking about all the different types of artists that express, essentially, violence or crime through their art and how many of those people maybe aren’t doing anything like that in their real life,” Stewart said. “I mean, I can’t think of a video game that doesn’t incorporate some element of violence in it, right? There’s shooting; there’s sword fighting; there’s fist fighting. There’s all sorts of violent media that exists.”

However, Lamparello says the admissibility of Williams’s lyrics in court depends on their potential to display criminal intent, not necessarily their efficacy as evidence of a specific crime.

“Even though that type of speech would otherwise be protected by the First Amendment, it’s not protected when it’s being used to support, or provide a factual basis for, a criminal prosecution,” Lamparello said. “In short: Words have consequences. If those lyrics are found to be relevant to proving, for example, the rapper’s intent, particularly, or as evidence of certain acts, then it’s certainly going to be admissible and probative of whether the intent existed or the acts were committed.”

This could start a precedent for this to be used in other cases.

“If you start opening that Pandora’s Box, now every Quentin Tarantino film is gonna be used as evidence against him for crimes that he may have committed — or may not have committed,” Stewart said.