Country music’s transition from a genre of the working-class people to essentially nationalist republican propaganda perpetuates a lack of representation within the genre, creates a safe space for bigots and unethically preys on the emotions of low-class people in the South.

My whole life, I have felt genuine embarrassment for enjoying country music — a feeling that is inevitable when artists like Jason Aldean use their music platform to spew racist rhetoric.

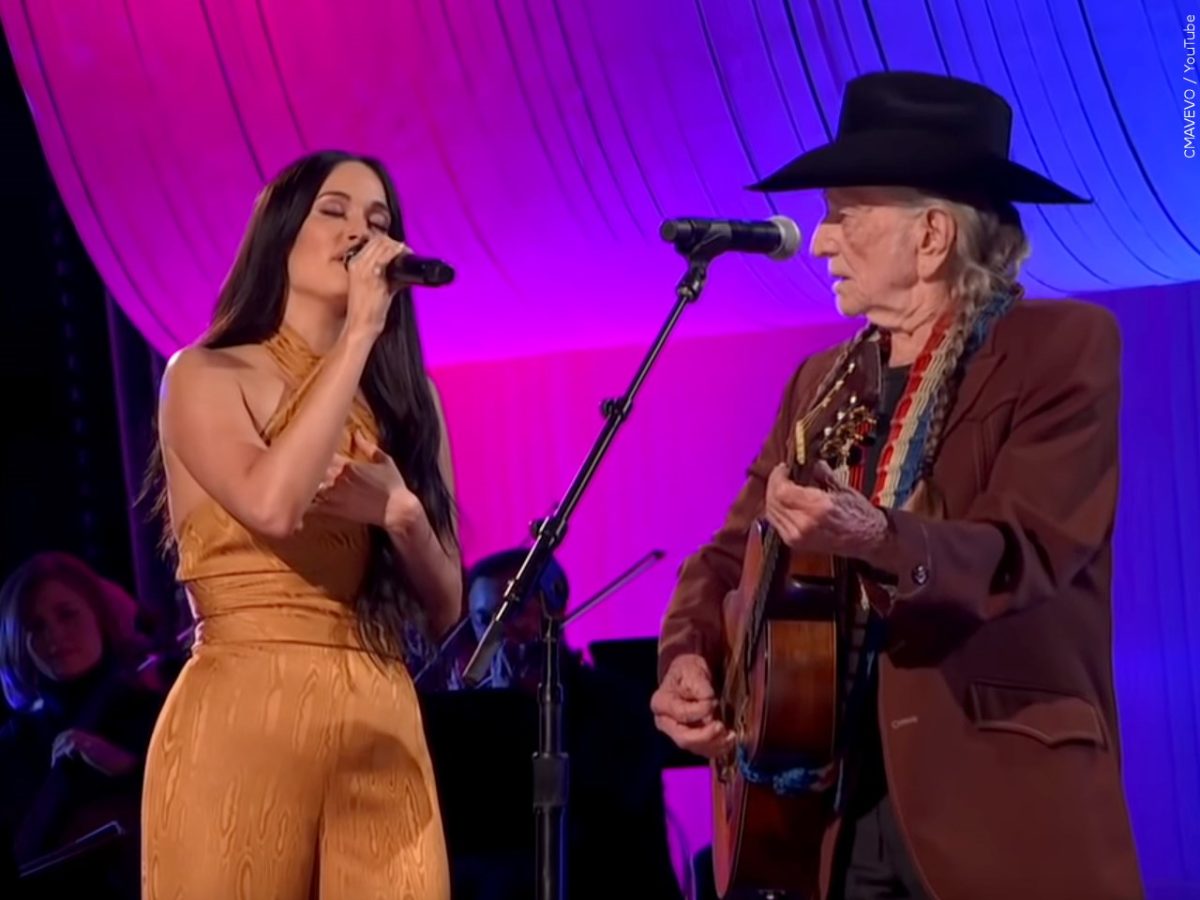

Although, the resurgence in popularity of country music that has been occuring in the past few years with new wave artists, such as Tyler Childers, Kacey Musgraves, Zach Bryan and Orville Peck, has been somewhat of a breath of fresh air to me.

It is disgraceful that country music is composed of primarily homogeneous identities, aka white straight men, and is associated with conservative values when this genre has such diverse roots. The modern-day country sound is a combination of genres, primarily traditional Irish music, but it was also shaped by African music, Mexican music and Hawaiian music.

Similar to almost every other popular genre in America, country music was appropriated by white people. For instance, the banjo was introduced to the United States by enslaved people, as it is an ancestor of the West African instrument the akonting. The banjo rose to popularity during the mid-1800s in minstrel shows, in which white people would make fun of slaves by dressing in blackface and playing the banjo.

In the 1920s, the first generation of country music acted almost as a medium to bring people together, with Black and white country musicians often collaborating. This pre-Great Depression period brought immense economic struggle in the South. The majority of farmers and coal miners were out of work, and the struggles that the working class experienced were highlighted in the music.

“Nearly 50 African-American singers and musicians appeared on commercial hillbilly records between those years — because the music was not a white agrarian tradition, but a fluid phenomenon passed back and forth between the races,” said Patrick Huber, a professor of history at Missouri University of Science and Technology, in the article “A Dive into the Black History of Country Music” by The Skidmore News.

When radios became popular during the Great Depression, so did Country music. The topics discussed within the music resonated with struggling Americans. Unfortunately, this commercialization led to the erasure of Black musicians in this genre, and it became designated as “white” music.

The third wave of country in the 1950s and 1960s paid homage to blues, jazz and gospel, an influence that is still apparent in the modern sound. This type of country is also referred to as “outlaw country” — my personal favorite.

Outlaw country sounds almost like a completely different genre than what has been playing on radio stations over the past few years. This almost pop-sounding country music, in which almost every song is focused on expressing pride for the South, is a direct result of consumer culture and the influx of Ameircan nationalism that began after 9/11.

The national trauma of 9/11 shifted consumers’ media habits. So, in return, country music adjusted to appeal to these needs, making way for artists like Toby Keith, Tim McGraw and Alan Jackson to become the kings of country music.

“They wanted more patriotic music,” said RJ Curtis, the executive director of Country Radio Broadcasters in 2001, in a Rolling Stone article. “And if you’re a good program director, you listen to what your fans want and give them more of it. If you put ‘U.S.A.’ or ‘America’ in a song, you had a pretty good chance of getting attention.”

Personally, I believe that this is unethical, as it is rich people pandering and abusing the fragile emotional state of fans. And, although some of the songs are awesome, these musicians are profiting off of the tragic loss of Americans while simultaneously spreading ignorant pride for a country that has repeatedly oppressed minorities.

This heightened commercial success of releasing songs about patriotism resulted in more artists tapping into this market, manifesting in a consumer-centric and money-hungry genre.

The South has the highest poverty rate of any region in the U.S., with over 20% of people in the rural areas having a low socioeconomic status. And since its birth, country has been the genre that embodied and gave a voice to these people experiencing economic turmoil.

In the early to mid-2000s, it felt as if artists were preying on the vulnerability of poor rural Southerners, with radio stations constantly playing songs about how amazing it is to be a farmer even though the singer has probably never even touched a tractor.

This infiltration of disingenuous artists making music that they do not relate to in hopes that it will appeal to audiences has made country music feel disingenuous. Over time, I think that the insincerity and lack of relatability became obvious to consumers, leading to the downfall in popularity.

In the past few years, it has felt as if there has been a stark divide in country. On one side, there are artists who produce this disingenuous pop, stereotypical country, and on the other side is the new wave of musicians.

Not only is the new wave creating music that seems genuine and is reminiscent of the outlaw country era, but there is also an increase in female and LGBTQ+ representation. Representation is — obviously — imperative for consumer retention since people consume content that is a reflection of their perceptions of themselves and the world around them, and this diversity has helped bring in new fans to this once extremely exclusive genre.

However, the lack of racial diversity of artists remains apparent. According to an article written by Variety, from 2000 to 2020, only 1% of musicians signed to the top three country music labels in Nashville were Black, and only 3.2% were BIPOC. Clearly, there is a lot of work to be done to ensure that this genre is a safe space for all people.

The status of genres often reflects the ideology among society at that time, and the evolution of country music truly confirms that although it might not feel like it, society is progressing — slowly but surely — in a positive direction.