The U.S. Citizenship test is nearly impossible to pass. That needs to end. Now.

April 5, 2023

Within the past few months, I have been required to take the Georgia and U.S. legislative tests that are required by state law to be completed by students pursuing higher education. Students must pass the test with a 60 or above to gain credit. If they fail in passing this test score after three attempts, they are required to take a course to compensate. After my first take of the Georgia legislative, I was shocked to find out how difficult and oddly specific the exam was. When the U.S. legislative test ended up being the same level of difficulty, I was frustrated. There really is no purpose in people needing to know obscure and random facts about a Georgia marsh to get their college diploma in a degree that is completely unrelated to history. When expressing these concerns to a friend, we began to wonder if these are the types of questions asked on citizenship tests. It also prompted me to think whether these tests should be necessary at all.

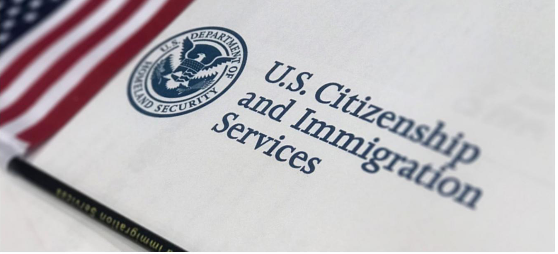

To some degree, it will always be important to understand the history of the entire world — to know where we came from and the history of our ancestors’ shapes, who we are and the changes we need to make as a new generation. Despite this, there is no justification for forcing people to learn hyper-obscure and random facts that they will not retain in the long run just for the sake of doing it. According to the New York Times article, “New US Citizenship Test is Longer and More Difficult,” by Simon Romero and Miriam Jordan, the new citizenship test is more difficult for those that do not speak English as their first language. The test is also longer and more challenging than before.

“The new citizenship test that went into effect on Tuesday is longer than before, with applicants now required to answer 12 out of 20 questions correctly instead of six out of 10. It is also more complex, eliminating simple geography and adding dozens of possible questions, some nuanced and involving complex phrasing, that could trip up applicants who do not consider them carefully,” Romero and Jordan said.

The addition of questions that are meant to confuse those that are learning or do not speak English is a tragic and awful attempt at working against immigrants. The majority of U.S. citizens do not have a clue about in-depth historical facts. There is no justification for expecting those trying to gain citizenship to know them either. The New York Times article further explained the motive behind this new test according to Eric Cohen, executive director of the Immigrant Legal Resource Center in San Francisco.

“There is no legal reason, no regulatory reason to do this,” Cohen said.

He noted that the citizenship test had remained unchanged since 2008.

“They decided on their own that they have to change it for political reasons,” Cohen said.

It is sad that this country can not seem to escape the superiority complex of singling out those trying to gain citizenship and putting them through a test that asks them unnecessary and silly questions. It is also a sad fact that many U.S. citizens are unaware of facts such as these until they are prompted to seek them out themselves.