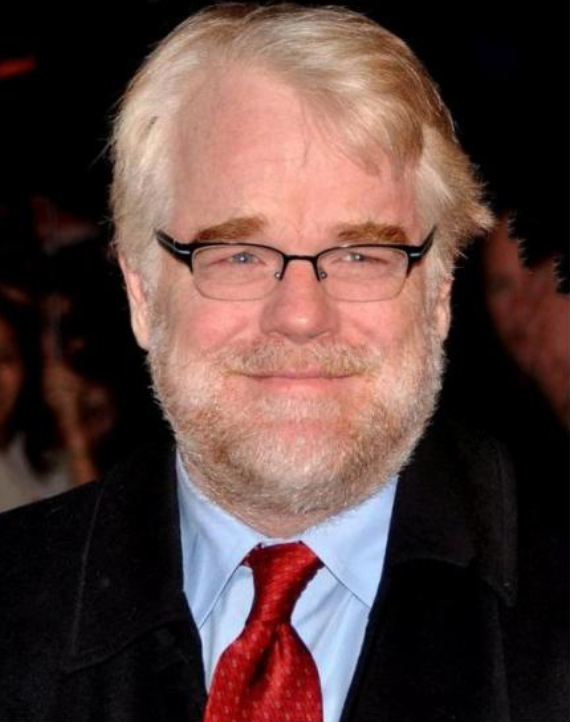

Cale’s cinema critique: remembering Philip Seymour Hoffman

February 22, 2023

On Feb. 7, the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, announced its plans to permanently display a bronze, life-size statue of the late, great Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Hoffman, who passed away at the age of 46 in 2014, is one of my favorite — if not my favorite — actors of all-time.

After reading a handful of articles on the museum’s plans to honor him, I found myself, once again, going down a YouTube rabbit hole, spending close to an hour watching bits and pieces of his old interviews and rewatching clips from my favorite performances of his.

Within minutes, I was in tears — and I felt weird about it. At the time of Hoffman’s passing, I was a 12-year-old with no idea who he was.

When Kobe Bryant, one of my childhood heroes, passed away in 2020, I felt as if my devastation was justified. Basketball was, for years, a cornerstone of my life. I can still remember sitting in front of my family’s small tube TV, watching Bryant win his fifth and final title with my father. The image of Bryant standing on the scorer’s table, looking out at the L.A. faithful, arms outstretched as confetti falls to the floor, is seared into my soul.

Yet, Hoffman’s impact on my love of film is not any different from Bryant’s impact on my love of basketball.

Paul Thomas Anderson is my favorite director of all-time, and he cast Hoffman in five of his first six films, including “Boogie Nights,” “Magnolia” and “The Master” — three films that are foundational for me.

It is hard to put into words exactly why I connect with Hoffman’s work as much as I do, but one thing is for sure: His range was undeniable.

Just within his handful of collaborations with Anderson, Hoffman mastered a myriad of peculiar personalities. As an oddball outcast, he steals the show from his big-name “Boogie Nights” co-stars, Mark Wahlberg and Julianne Moore. In “Magnolia,” he stands out amongst an all-star ensemble — which includes prime Tom Cruise — as an angst-ridden nurse. He finds himself screaming at Adam Sandler — a tall task in and of itself — in “Punch Drunk Love.” Oh, and in “The Master,” he joins Joaquin Phoenix — one of the best actors, if not the best actor, of his generation — in an eerie exploration of manipulation and power.

Yet, despite his all-time acting pedigree and plethora of roles in high-brow productions, Hoffman was far from pretentious. He gives just as powerful of a performance in J.J. Abrams’s “Mission Impossible III” as he does in the Coen brothers’ comedic classic “The Big Lebowski.” Whether he was on the set of a big-budget blockbuster or an austere Oscar contender, Hoffman’s esteem for each project was ever-present.

I am often reminded of Hoffman’s acceptance speech for his one Oscar, which he won for his leading role in Bennett Miller’s “Capote.” In a matter of mere seconds, he thanked a handful of his loved ones, including his mother, for their support, and he rushed off the stage, as if he was scared of the spotlight beaming down on him. He did not attempt to deliver a grand, sweeping provocation on the art of acting — because he did not need to. He left it all on the screen.

Rest in peace, Mr. Hoffman.