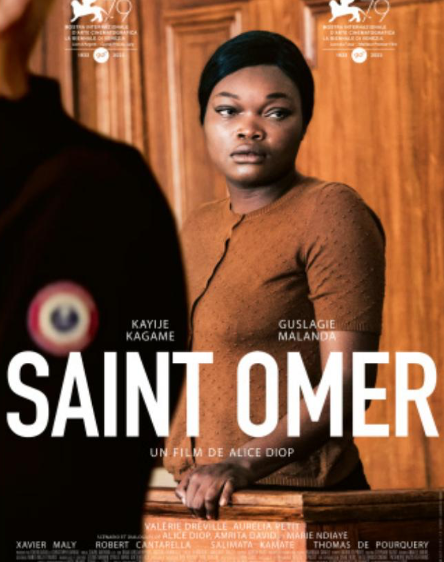

Cale’s cinema corner: “Saint Omer”

A courtroom drama that begs the question: Do we blame the system or the person?

February 20, 2023

Courtroom dramas often withhold the jury’s verdict until the film’s final minutes, allowing the first and second acts to build tension, often through an intellectual game of cat-and-mouse between the accused and the accusers. In the opening act of Alice Diop’s first feature film, “Saint Omer,” the defendant admits to committing the crime of which she is accused. Less than 30 minutes into the film’s runtime, its core tension appears to be resolved.

Yet, Diop’s narrative gains, rather than loses, momentum in the aftermath of Laurence Coly’s confession. As the central question of her trial is answered, countless others emerge, all of which are fueled by an unconditional longing for understanding.

The film’s final 90 minutes center on the pursuit of its protagonist, Rama, played by Kayije Kagame, to comprehend Coly’s crime. Rama is an aspiring author and literature professor who comes to Coly’s trial in search of inspiration for her next novel, a modern spin on Euripides’s “Medea.” Rama is also a stand-in for Diop, whose experiences attending the 2016 trial of Fabienne Kabou inspired the film.

On the surface, Rama and Coly’s lives parallel one another. Both are intellectuals and invested in the world of academia. Both have complicated relationships with their mothers and their heritage. Both are in interracial relationships. Both are Senegalese-French women — and the only Black women, aside from Coly’s mother, present at the trial.

Regardless of Coly’s confession, the judge presiding over the Berck-sur-Mer courtroom, played by Valérie Dréville, is not concerned with punishing the defendant for abandoning her 15-month-old daughter on the beach of Saint Omer. She is interested in who she is — as a daughter, a student, a partner and a mother.

At first glance, Coly’s story is confounding. She is a PhD student. She is well-spoken. She cites René Descartes and Ludgwig Wittgenstein during her defense — which a juror confronts her about, as he assumes a Senegalese-French woman would be interested in philosophers “closer to her own culture.”

However, even after admitting to her crime, Coly’s resolve remains. She does not believe she is responsible for the murder; demons are.

Further interrogation gives context to Coly’s struggles. Out of financial desperation, she, a poor student, entered a loveless relationship with a married, middle-aged man, which led to her daughter’s birth. He left. Out of shame, she confined herself within the walls of her house, in which her daughter was born. No one was aware of her daughter’s existence.

The world was introduced to her as a washed-up corpse.

Despite the defendant’s detailed, disturbing description of her daughter’s death, Diop does not end “Saint Omer” with the verdict of Coly’s trial. We do not know if the court’s compassionate judge accepted her defense. If she was convicted, we do not know how harsh or merciful her sentence is — because, in the end, it does not matter.

Before the film fades to black, we see Rama, devastated and pregnant, holding hands with her estranged mother. She is distraught — not just because of the macabre nature of the murder, but because it could happen to her.