Preserving the dark history of Central State Hospital

Marissa Marcolina | Digital Media Editor

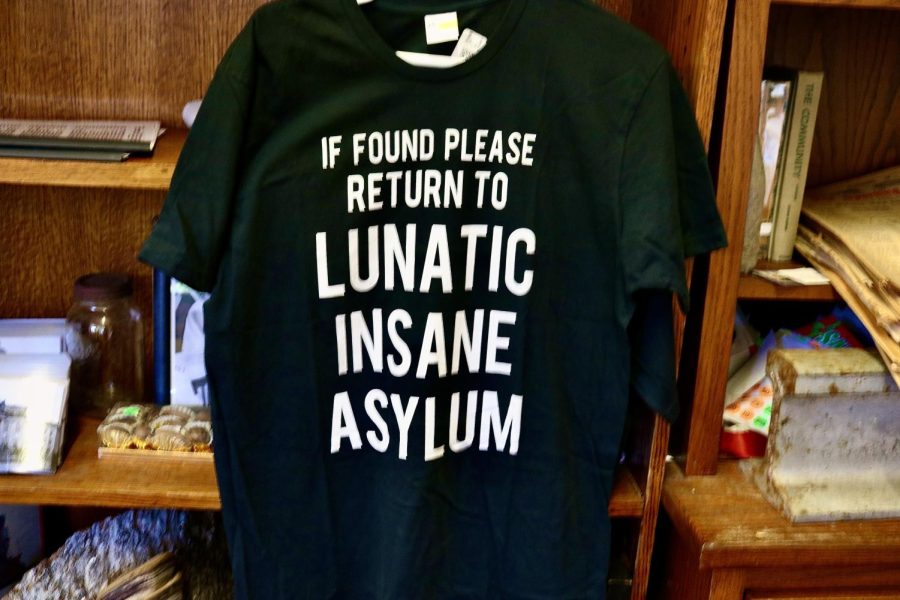

One of the items being sold at Auntie Bellum’s Attic in downtown Milledgeville.

September 28, 2022

Auntie Bellum’s Attic, an antique store in downtown Milledgeville, is currently selling items from Central State Hospital. Before its closure in 2009, this hospital was the largest asylum in the United States, but it holds a disturbing past of racism and abuse.

There is an extensive list of reasons a person could be admitted into Central State in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. A person could be admitted for reasons such as asthma, laziness, suppression of ideas about masturbation, enthusiasm about religion, spending time in war, menstrual cramps, being kicked in the head by a horse, leaving their husband, ill treatment by husband and many more reasons. These reasons for admission were disproportionately used to put African Americans and women into the facility.

Mab Segrest, author of Admission of Lunacy: Racism and the Haunting of American Psychiatry at the Milledgeville Asylum, spent 15 years researching this hospital.

“Through my reserach, I realized this was a narrative about racism and the effects and afterlives of slavery which are still so prevalent in the south today,” Segrest said. “Not only on this asylum, but on psychiatry itself.”

Patients were segregated until the 1960’s. According to Segrest, there were issues of overcrowding in the building that housed the black patients. Patients in the black building, especially black women, received significantly less necessary supplies than the white patients received. In the late 1800’s, a fire burned down the black patient’s housing which resulted in one death and many patients getting tuberculosis.

“I’ve compared this fire with some asylum fires in Ohio and in the north, and their patients were taken into peoples homes and churches and cared for,” Segrest said. “Whereas, these black patients were put in prisons or in the tunnels under the campus.”

When the black patients building was rebuilt, the new building included a new facility where inhumane medical practices on specifically black women took place. This building of horrors was glossed over in the Ga. state records that Segrest examined.

“I had to read these documents very closely before I would catch things,” Segrest said. “What they did was add this little building to do surgeries, gynecological surgeries. And what was that? That was hysterectomies. So, they were starting very early as the legacy of the fire and the building, having a surgery for eugenic sterilization.”

White patients were subjected to abuse in this facility as well, however, black patients were subjected to unfathomable horrors. When discussing these disparities, Segrest referenced an article written by Ebony Magazine in the 1940’s that equated the white patients experience to prison and the black patients’ experience to a Nazi concentration camp.

Working at Central State was one of the best paying jobs with the most benefits in central Georgia; therefore, until its closure, it was the biggest employer in Baldwin County.

“It was like its own little town,” Croft said. When you’re talking about employees of Central State, you’re not just talking about nurses and doctors.You’re talking about dentists, firemen and people who served food. One of the largest kitchens in the United States is at Central State.”

By the 1960’s, many of these workers were passionate about helping these patients, but unfortunately, even the people who came to this hospital for good reasons were traumatized. Richard Brookins, a friend of Segrests, came to Central State in the 1950’s in hopes of helping people in need, but on his first day of work he experienced the first of many traumatizing events.

“It was August, very hot, and the heating system ran under the building, but for some reason the heat was still running and the doors were locked,” Segrest said “32 people died that night. It’s not so clear if they just died there or if something was happening across the campus. I looked in the records, and I could never find it.”

Horrific stories like this are often not in the official documentation the state of Georgia has on this hospital. Holly Croft, GC’s digital archivist, condemned the way the state has documented Central State’s past.

“I think Milledgeville itself has done a lot of omission with the story of Central State,” Croft said. “There are periods of time where Georgia was really proud of Central State, and periods of time where they have not been proud of it. The records reflect that.”

Similar to the stories of the patients, the stories of these workers are lost. After receiving a grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services, Croft is working alongside Evan Levett to record stories of past employees.

“Oral histories are wonderful but also you wish that there was more documentation,” Croft said. “You’re doing the oral history to create the documentation for something that should already exist. That’s just not out there.”

According to Croft, there is not a lot of stuff about Central State at the GC library. The library has a few books and some annual reports, but they do not have many resources.

There used to be a small museum at The Depot that had some resources about Central State hospital, but this museum is no longer in use. Now, the museum is being moved to the Central State campus. This museum will include the materials from the old Georgia capitol building, but according to Segrest, the section about Central State will shrink dramatically.

“The state of Georgia is not invested in letting people know what happened, from the state point of view,” Segrest said. “By the time I left, all the documents I had gone through in that museum had been stacked up and put away in one of the administration offices, and you couldn’t get access to them.”

To share and preserve history, history preservationists such as the Auntie Bellum’s Attic antique shop in downtown Milledgeville have collected items from the hospital. Larry Houston, the owner of Auntie Bellum’s Attic, received this collection from one of his vendors, Edwin Adkins. This Central State collection includes photos, a replica of an old electric chair, t-shirts with quirky logos on them, old documents and paintings.

“They just got rid of all the stuff afterwards,” Houston said. “I imagine there’s a ton of stuff still out there.”

There are 25,000 unmarked graves on the property. Some of them are just marked by a number while some of them have no marking at all on them. These patients’ entire existence was reduced to a simple number, but they were real people whose lives ended unfairly.

Now, Central State is seen as an abandoned ghost town that is just rotting away, but the real ghosts are the patients and workers who were forgotten. Because this was once the largest hospital in the U.S., it has impacted thousands if not millions of people as well as influenced the way psychiatry is practiced, and this history is being lost. In order to prevent these peoples stories from being lost and to prevent these injustices from ever happening again, this history, especially the bad parts, must be acknowledged, taught and preserved properly.

“We have to stop entertaining this fiction that it happened 100 years ago, and we have no responsibility for those events,” said Mark Huddle, professor of African American history and popular culture. “Without that acknowledgement, there can be no reconciliation. Without reconciliation we cannot create a more equitable society.”