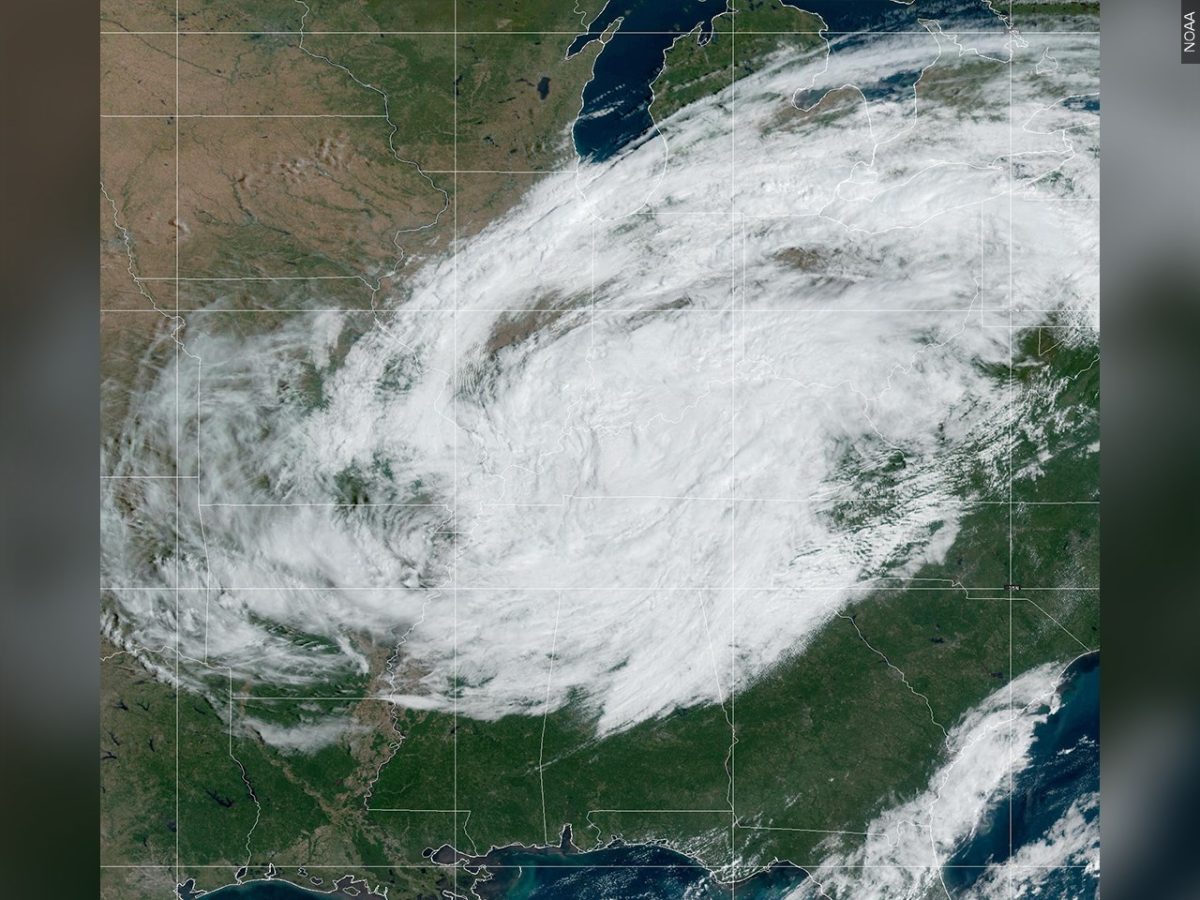

The 2024 Hurricane Season has decidedly wreaked havoc across much of the southeastern United States. The late September wreckage caused by Hurricane Helene was truly catastrophic for the Carolinas, but Georgia and Florida were nowhere near unscathed. Milton pummeled Tampa Bay just days later but mercifully limited its destruction to the peninsula. August’s Hurricane Beryl is not to be forgotten, as it too was a major storm that drenched Texas.

In May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, released its predictions for the upcoming storm season. NOAA forecasted an “above-normal” Atlantic season, estimating anywhere from 17 to 25 named storms, of which between eight and 13 were predicted to strengthen into hurricanes. Between four and seven of those hurricanes were expected to be major, which means they were classified as a category three or higher with winds of at least 111 miles per hour.

As of Nov. 4, records indicate that there have been 17 named storms this season. Seven have been tropical storms, including Tropical Storm Raphael, though current projections expected it to strengthen into a hurricane. There have been a total of ten hurricanes, four of which are classified as major hurricanes — Beryl, Helene, Kirk and Milton. The lesser-known Hurricane Kirk was a Category 5, but it did not make landfall in the U.S.

“Tropical cyclone activity this October was above average in terms of the number of named storms and hurricanes that formed in the basin,” said NOAA’s Monthly Atlantic Tropical Weather Summary for October. “Four named storms formed in October with three of them becoming hurricanes, and one of those becoming a major hurricane (Milton). Based on a 30-year climatology (1991-2020), two to three named storms typically develop in October, with one of them becoming a hurricane and a major hurricane.”

As global warming has increased ocean temperatures across the globe, scientists have paid close attention to the relationship between warmer waters and hurricane intensity. Most agree that there has not been a noticeable uptick in the total number of storms developing each season, but the storms that develop are more powerful and, therefore, can be more destructive than storms born in cooler oceans.

“Due to climate change, the oceans are absorbing a lot of heat because that’s what water does,” said Dr. Doug Oetter, professor of geography. “And when it holds on to that heat, it has to be released. It can be released through currents, but the Gulf is kind of isolated, so the currents have a hard time getting into that gulf loop. So the heat tends to remain there.”

Rapid intensification is when a hurricane jumps from a lower categorization, such as one or two, into a three, four or even five in a relatively short time frame. Specifically, when a storm increases speed by at least 35 miles per hour in a 24-hour window, the jump is deemed rapid intensification.

Hurricanes categorizations are determined by wind speed. A Category 1 storm is between 74 and 95 mph, according to NOAA. If a 95 mph storm increased by 35 mph, it would be a Category 4 storm, which has winds from 130 to 156 mph. And a storm having a four-category increase in 24 hours is definitely attention-grabbing. Last month, Milton increased speed by 95 mph in 24 hours, making the jump from Category 1 to 5 in a day.

Hanna Sowers is a senior double majoring in history and geography. She is from Rincon, a coastal town near Savannah, giving her more experience than most Georgians when it comes to bracing for hurricanes and tropical storms. She recalls Hurricane Matthew being particularly damaging to the region, leaving her family without power for several days and uprooting many of Savannah’s iconic oak trees.

Matthew was a powerful Category 5 storm in 2016, and it too intensified quickly. Though it had weakened to a Category 1 when it made landfall in South Carolina, the system lingered just off the coast, sending flooding and torrential rain into Georgia.

Though attacking the state in a different fashion, Helene, too, did not spare Rincon when she blew through.

“We had a tree fall on our house,” Sowers said. “It was kind of just sitting on our roof. And I know people who went for two weeks without power. My school system was out for a week, so it was pretty bad.”

Helene was originally predicted to follow the Georgia-Alabama border on its journey inland, but it switched directions, with Milledgeville lying directly in its path. Though many students expected this to mean devastation to the city, it was truly east Georgia that ended up taking the brunt of Helene’s assault.

“[The east side] is the leading edge of the hurricane,” Oetter said. “So as the hurricane is moving very quickly, I believe it was like 30 miles an hour, that adds to the winds, which were over 100 [mph]. So now we have 130 [mph] on the east side of the hurricane, but 70 [mph] on the west side because there, the winds are moving against the forward motion of the storm.”

Helene’s shift east may have appeared to put Milledgeville on a more direct path, but to a trained eye, this actually may have saved the city from more devastating damages. Had Helene continued on the original projected path northward through west Georgia, Milledgeville would have been subject to that eastern leading edge, where winds are stronger. But because the city found itself west of Helene’s eye, it suffered less harm than eastern cities like Augusta and Statesboro.

2024 sent mighty storms inland, but hurricane season does not end until Nov. 30. As of Nov. 4, Tropical Storm Raphael is developing and is predicted to intensify into the seventh Atlantic hurricane of this season.

“Gulf hurricanes in November are relatively uncommon — there have only been five in the last 25 years,” Oetter said. “Rafael is set to strengthen through the week and could impact the Gulf Coast by Thursday or Friday. The current prediction is for the storm to lose some strength before landfall, but conditions should be monitored carefully as it interacts with the Loop Current in the gulf.”

As far as advice goes, senior geography major Nick Wheeler recommends that people listen to experts and make an effort to be informed.

“If [officials] say you should leave, you should probably listen to them because they’ve done research, and they know that there’s a very strong likelihood of you not surviving, you getting injured or you losing property and belongings,” Wheeler said.

Wheeler also recommends taking courses in the Geography Department to learn more about climate science surrounding hurricanes. He recommends Intro to Weather and Climate, which Oetter teaches, and Natural Hazards.

From a big-picture standpoint, Oetter is optimistic that climate change can be addressed through collective action and finds that the biggest hurdle nowadays is not so much “climate deniers” but those who feel that they alone cannot make significant enough of a difference so they do not bother to try.

“We are a commuter college, and we don’t deserve to be a commuter college because we really should have more people walking, biking and taking shuttle buses to campus,” Oetter said as an example of how students can make small lifestyle changes that make real differences. “Instead, we have over a thousand people driving every day.”

Warming waters are leading to real, detrimental effects for those who live in the paths of hurricanes. The 2024 season has shown Georgia and its neighboring states what kind of damage powerful storms can wreak, and it may not be over yet.